As I see it, there has been a huge revolution in economics over the past 35 years or so.

But it wasn't a change in the dominant econ theory. Theory has certainly changed, sure, but more by evolution than revolution - things like game theory and behavioral theory have slowly been mixed in with the old hyper-rational "neoclassical" paradigm.

No, the big revolution has been in the role of theory itself. Go back and read some old 1970s papers (I'm not going to link to any specific ones, following my policy of not singling out specific authors), and you'll be amazed at the disconnect from reality. A lot of those papers would take great pains to specify that the outcome space was assumed to be a Borel space, while spending precisely zero time discussing how the model could be tested against real-world data. This was econ's famed "deductive method" at its most arrogant. It really was enough to just show up, state your assumptions (i.e. herp your derp), solve the resultant math problem to get some nice-looking equations, and call it a day.

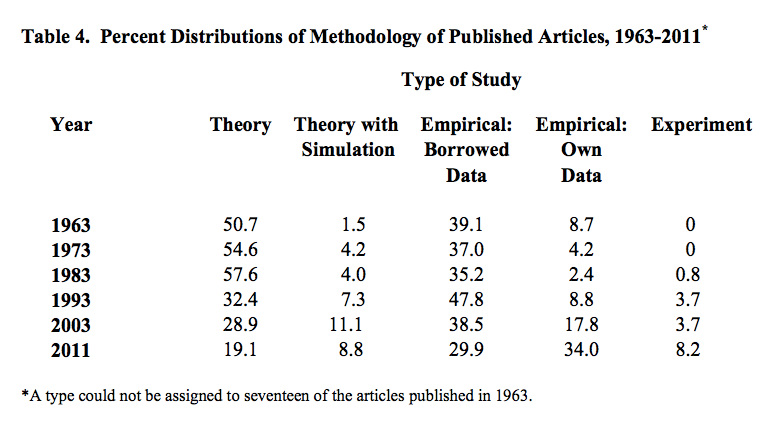

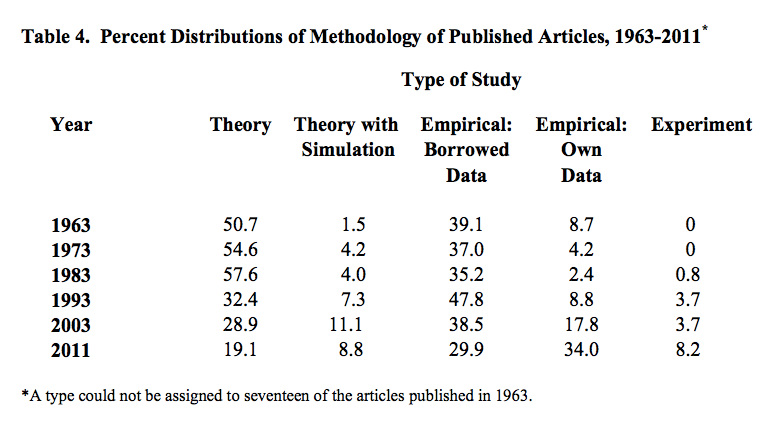

That doesn't seem to be so true anymore. Theory papers peaked as a percent of the total sometime between 1973 and 1993, and have been declining ever since:

That's a very dramatic drop. And notice that a lot more theory papers nowadays include simulation.

A lot of people can feel the wind changing. "Theory is kind of dead," Tyler Cowen once told me over drinks (beer for me, soft drink for him). "Nothing big is coming out of theory these days." "What about social learning and herd behavior?", I countered. "That was sort of the last gasp of theory," he said with a grin, "and it was twenty years ago."

Macro has been slower to embrace the change, because macro data is so uninformative that often all you can do is spin one theory after another. But macro also seems to feel the pressure. "We don't really need more macro theorists," a prominent macroeconomist once told me. "What we need are macro empiricists."

I call that a revolution. It's not quite a Thomas Kuhn style paradigm shift - more of a shift in the underlying criteria that the economics community is using for deciding how the world works. Deduction is on the way out, and induction is on the way in.

Why did this happen? I'm not sure, but my guess is that the meteor that hit the economics dinosaurs, and set the field's evolution off in a new direction, was named Daniel Kahneman. Starting in 1973, Kahneman released a torrent of papers showing that human behavior didn't look anything like the way that homo economicus was supposed to act. Other behavioral meteors followed. There was Richard Thaler, who showed how behavioral effects could mess up many of the decision-making processes in economics. There was Vernon Smith, who showed that even simple markets don't work the way economists long assumed. There was named Colin Camerer, who scanned people's brains and confirmed that non-rational decision-making processes were at work. There were many others. Really, it was a giant comet of Behavioral Economics that broke up somewhere in orbit and fell to Earth in many parts.

As the weight of evidence mounted, the economics community could no longer ignore the contradictions between theory and reality. But though they had found a swarm of factual anomalies, the behaviorists failed to produce a new grand theory to replace the hyper-rational paradigm their empirical work had smashed. Even simple, limited theories like Prospect Theory have struggled to make sense of the world outside the lab. The ship of economics hasn't so much been pointed in a new direction as set adrift without a compass.

Of course, this was probably inevitable. The old hyper-rational theory was unified only because it dramatically oversimplified the world. But it could only oversimplify the world because it refused to look at the world. As soon as someone came along and forced economists to look out at the world, most of the work that economists had done had to be discarded. (Not all, interestingly; the pure-rational-deductive approach has had a few stunning successes.)

So what do you do when you can't make sense of the world? You just keep trying to get a better picture of the world. My guess is that this is why econ is shifting from theory to empirics.

But I also see econ's shift as being part of a bigger, deeper change that is happening all across academia. In physics, fundamental theory has hit a wall. The Standard Model, completed in the 70s, has been well confirmed by experiments, and all the leading candidates for new physics seem to be untestable. Even in math, formal deductive proof is slowly being replaced by proof-by-computer; at some point the question of whether math is an empirical science gets harder to answer definitively. As for the humanities, "theory" has basically become a giant joke, even if a lot of leading scholars haven't gotten the joke yet. Meanwhile, a lot of the big revolutionary advances seem to be coming in biology, while the other "lab sciences" of chemistry, materials science, neuroscience and electrical engineering continue to rack up steady progress. And "data science" is considered the new frontier. Obviously all these fields make use of existing theories, but they rarely tend to cook up dramatically new theories, or to work in "deductive", theory-first paradigms.

Maybe humanity is reaching the end of a big Theory Wave. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw such enormous victories for theory - Cities destroyed! Thinking machines invented! Logistics revolutionized! Chemistry reinvented! - that we poured a lot of our brainpower into sitting down with pencil and paper and working out mathematical ideas about how the world might work. Maybe we've temporarily exhausted the surplus gains available from ramping up our investment in theory, and the boom is quietly coming to an end.

But that's just my theory. To back it up, I'd need some better data.

Update: A number of people have suggested that the supposed decline of economics theory is really just an explosion of empirical work due to the decline in the cost of computing and the increase in the supply of publicly available data. I certainly do believe that a decline in the cost of computing has led to an explosion of empirical work. However, here are some points that suggest that the "theory is dying" hypothesis has some legs:

1. In the past, increases in the supply of data (from new experimental techniques and from earlier improvements in computing power) have sparked simultaneous booms in theory, as theory was needed to explain the new data gathered. I don't think we see that happening in econ.

2. Currently, experiments are rising as a share of published papers. The cost of experiments is mostly subject fees, not the cost of computing.

3. According to a similar study by Card and Della Vigna, the absolute number of papers published in top journals has fallen. this means that the total number of theory papers, not just the percentage, published in top journals has fallen. If an explosion in empirics due to cheap computing had simply outpaced a more gentle increase in theory papers, we would expect to see the top journals increase their number of papers, or for new top journals to emerge. Instead, neither has happened. In fact, the failure of the computing boom to lead to more top-journal papers is a puzzle in and of itself.

4. As seen in the Hammermesh study, the percent of top-journal publications doing empirical analysis on borrowed data has also decreased recently, despite the increase in the supply of such data.

5. According to Card and Della Vigna, The frequency of citations for "theory" papers (which means pure micro theory, and so doesn't include all theory) is falling relative to other fields.

Now, it may be the case that top-journal publications are simply a bad guide to how much is getting discovered. Much more good research may now be getting published in lower-tier journals. Or perhaps the fraction of truly important research in even top journals was always small, so trends in total top-journal publication might not reflect trends in truly important results.

In that case, all we have to go on are anecdotes and the zeitgeist within the profession.

Update 2: Paul Krugman's anecdotal evidence agrees with mine - theory is becoming less important in trade and macro. He has different hypotheses about the cause, however.

Update 3: Tony Yates (whose blog I just now discovered, thanks of course to Mark Thoma) disagrees, and thinks that macroeconomic theory is alive and well. I think he does have a good point; macro seems to have resisted the shift to empiricism more than the other econ sub-fields. Of course, Yates and I would probably disagree on whether or not that is a good thing.

Update: A number of people have suggested that the supposed decline of economics theory is really just an explosion of empirical work due to the decline in the cost of computing and the increase in the supply of publicly available data. I certainly do believe that a decline in the cost of computing has led to an explosion of empirical work. However, here are some points that suggest that the "theory is dying" hypothesis has some legs:

1. In the past, increases in the supply of data (from new experimental techniques and from earlier improvements in computing power) have sparked simultaneous booms in theory, as theory was needed to explain the new data gathered. I don't think we see that happening in econ.

2. Currently, experiments are rising as a share of published papers. The cost of experiments is mostly subject fees, not the cost of computing.

3. According to a similar study by Card and Della Vigna, the absolute number of papers published in top journals has fallen. this means that the total number of theory papers, not just the percentage, published in top journals has fallen. If an explosion in empirics due to cheap computing had simply outpaced a more gentle increase in theory papers, we would expect to see the top journals increase their number of papers, or for new top journals to emerge. Instead, neither has happened. In fact, the failure of the computing boom to lead to more top-journal papers is a puzzle in and of itself.

4. As seen in the Hammermesh study, the percent of top-journal publications doing empirical analysis on borrowed data has also decreased recently, despite the increase in the supply of such data.

5. According to Card and Della Vigna, The frequency of citations for "theory" papers (which means pure micro theory, and so doesn't include all theory) is falling relative to other fields.

Now, it may be the case that top-journal publications are simply a bad guide to how much is getting discovered. Much more good research may now be getting published in lower-tier journals. Or perhaps the fraction of truly important research in even top journals was always small, so trends in total top-journal publication might not reflect trends in truly important results.

In that case, all we have to go on are anecdotes and the zeitgeist within the profession.

Update 2: Paul Krugman's anecdotal evidence agrees with mine - theory is becoming less important in trade and macro. He has different hypotheses about the cause, however.

Update 3: Tony Yates (whose blog I just now discovered, thanks of course to Mark Thoma) disagrees, and thinks that macroeconomic theory is alive and well. I think he does have a good point; macro seems to have resisted the shift to empiricism more than the other econ sub-fields. Of course, Yates and I would probably disagree on whether or not that is a good thing.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar