In my last post, I claimed that the main theoretical framework that people use to think about the Japanese stagnation - the mainstream Woodford New Keynesian model and its baby brother the Econ 102 AD-AS model - didn't apply, because prices couldn't be sticky for 20 years. Paul Krugman agreed that the standard model is inapplicable, but took me to task for forgetting about the liquidity trap.

I didn't forget about the liquidity trap. I just didn't talk about it. Why? Because it's not what most people are using to think about Japan. A liquidity trap may look like something you can just tack on to a standard Woodford or AD-AS model and obtain mostly the same results...but really, it changes the whole thing. And most macroeconomists (that I have seen) are not paying a ton of attention to the Zero Lower Bound; they are still thinking about things in the AD-AS or Woodford paradigm, where unemployment involves things like sticky wages. So that was the paradigm I wanted to address in my earlier post.

I should say that although I haven't ground through the mechanics of a liquidity-trap model, I am favorably disposed toward the models. Why? Because they seem to fit some important stylized facts. The idea of the "paradox of thrift" seems to match what we saw in the U.S. after the 2008 crisis; American savings rates spiked but inflation fell and growth fell, making the resultant deleveraging relatively modest. And the idea that the Zero Lower Bound is real and important seems borne out by the difficulty that central banks have had in creating growth or inflation via Quantitative Easing. Certainly, liquidity trap models are consistent with one important piece of the Japan story: the coupling of persistent deflation with zero nominal interest rates.

As I said in the update to my last post, liquidity trap models might be able to explain Japan's stagnation where mainstream New Keynesian/AS-AS models fail. Liquidity trap models might have multiple equilibria, or very very long-lasting impulse responses to demand shocks. I'm not sure whether they do have these features, but it seems that they might. And they might contain some reason why Japan might be more susceptible to a super-long deflation than other countries.

BUT, here is the thing about liquidity trap models: They are not yet well-developed or well-explored, compared to other kinds of models. The liquidity trap is the subject of only a few theoretical papers that I know of. The main fully-specified NK-with-liquidity-trap DSGE model I know of - Eggertsson & Woodford 2003 - doesn't even include capital investment or supply shocks. And very few researchers have yet tried to take the model to the data to see how well it fits in general (as opposed to simply "explaining" the stylized facts it was invented to explain). This is in contrast to the Woodford/AD-AS paradigm, which has been very thoroughly explored by many many macroeconomists for decades. We know all about how Woodford/AD-AS works. But there are many things about liquidity trap models that we don't yet know or understand. And these gaps lead to puzzles when we try to apply the theory to the real world, even in a casual manner.

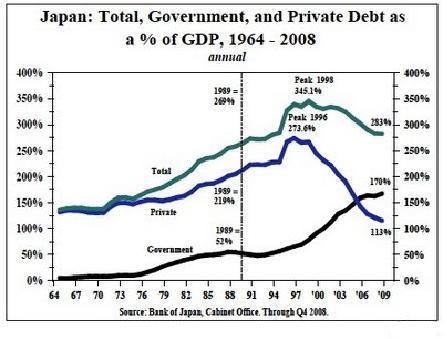

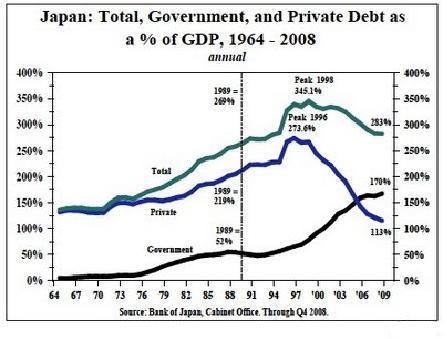

For example, the strong form of the Paradox of Thrift says that the private sector's attempts to save more will mostly be thwarted. But Japan has successfully deleveraged since its 20-year deflation began! Check it out:

That is a huge, steep, sustained fall in private-sector debt (the blue line) starting in about 1999 (note that it's a debt/GDP ratio, so this is in real terms). By the eve of the 2008 crisis, Japan's private debt was lower than at any time since 1964. And all through that successful rapid deleveraging, there was indeed deflation. And after that massive deleveraging, deflation or ~0% inflation continued.

That's not a result you would expect from knowing the Paradox of Thrift. It may well be that this sort of thing can happen in a liquidity trap model - it may not be a true "puzzle" or "anomaly" - but you wouldn't guess this from the basic intuition.

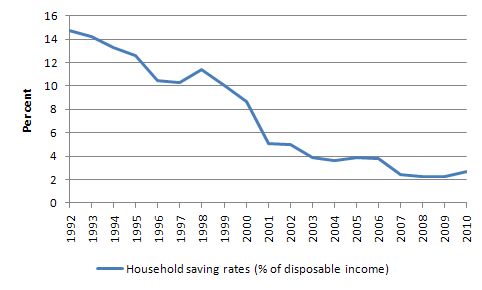

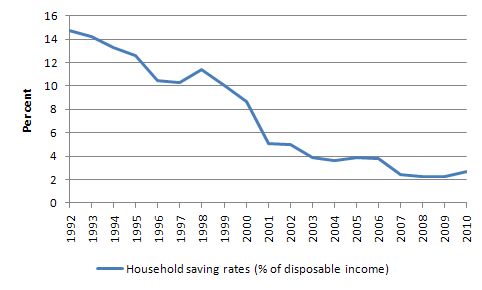

Another Japan puzzle for liquidity trap models is that Japanese households don't seem to behave the way that the models expect them to. During Japan's long deflation, household saving rates fell dramatically:

This is NOT what households are supposed to do in a liquidity trap, right? Japan's increase in private saving has all come from corporations. And I suppose you could wave a hand and say that the "representative household" owns the "representative firm" and makes corporate savings decisions. But even with increased corporate saving, Japanese savings rates fell during the deflation:

To my knowledge, liquidity trap models don't (yet) model the saving behavior of firms, since they don't (yet) include capital investment. They also don't (yet) model the effects of supply shocks in a liquidity trap; this is probably relevant for Japan, since its economy experienced a boom in 2002-2006, probably driven by increased trade with China, during which time interest rates and inflation both stayed around zero. Therefore, though falling private savings rates might not fit with the basic Eggertsson & Woodford (2003) liquidity trap model, it is not yet known if this would present a puzzle for an expanded, generalized model.

To my knowledge, liquidity trap models don't (yet) model the saving behavior of firms, since they don't (yet) include capital investment. They also don't (yet) model the effects of supply shocks in a liquidity trap; this is probably relevant for Japan, since its economy experienced a boom in 2002-2006, probably driven by increased trade with China, during which time interest rates and inflation both stayed around zero. Therefore, though falling private savings rates might not fit with the basic Eggertsson & Woodford (2003) liquidity trap model, it is not yet known if this would present a puzzle for an expanded, generalized model.

But that aside, here is really my fundamental issue. In a standard Woodford New Keynesian model, we know how long recessions can be expected to last without policy intervention: less than 5 years. In the liquidity-trap models, the characteristic length of a recession without policy intervention is not clear. Do recessions always go away on their own in a liquidity trap model, or does the economy get stuck indefinitely in a "bad equilibrium"? And recessions do go away on their own, how long does that usually take? I think this question needs answering before liquidity-trap models become our mainstream, go-to intuition about how the macroeconomy works.

Eggertsson & Woodford (2003) include some impulse response graphs, and it definitely looks like the effect of a shock decays in less than 5 years, just like in a standard Woodford New Keynesian model. However, those impulse responses are conditional on a policy regime that may not match what we see in real life. So the answer to the question of "How persistent are demand shocks in a liquidity trap model?" remains unanswered.

If it turns out that DSGE liquidity trap models don't produce stable "bad equilibria" or very very persistent impulse responses to demand shocks, then explaining Japan's 20-year-stagnation with one of these models will require the assumption of a whole string of negative shocks...just like their mainstream New Keynesian and RBC cousins.

Eggertsson & Woodford (2003) include some impulse response graphs, and it definitely looks like the effect of a shock decays in less than 5 years, just like in a standard Woodford New Keynesian model. However, those impulse responses are conditional on a policy regime that may not match what we see in real life. So the answer to the question of "How persistent are demand shocks in a liquidity trap model?" remains unanswered.

If it turns out that DSGE liquidity trap models don't produce stable "bad equilibria" or very very persistent impulse responses to demand shocks, then explaining Japan's 20-year-stagnation with one of these models will require the assumption of a whole string of negative shocks...just like their mainstream New Keynesian and RBC cousins.

So to sum up: No, I did not forget about the liquidity trap. And I kind of like the liquidity trap idea. I think liquidity traps are a candidate explanation for how demand shocks might have extremely long-lasting effects. But I do not know enough about the models to say that Japan's unusual situation can be explained by demand shocks + a liquidity trap. If the models require a long string of exogenous, hard-to-observe negative demand shocks in order to produce what we've seen in Japan, then I'm going to be very very skeptical. If, on the other hand, the models give some reason why some special Japanese characteristics - Shrinking population? Stagnant productivity? High levels of "patience"? - make a 20-year response to a single big demand shock a conceivable reality, then count me as a (tentative) believer.

Update: Steve Williamson and Matthew Martin both chime in with good posts that play around with the implications of liquidity-trap New Keynesian models. Both posts show how little of the standard New Keynesian intuition applies with liquidity traps, and how little we understand about the true general behavior of these models.

Update 2: Someone also reminded me of this paper by Mertens & Ravn, who find that liquidity trap models can sometimes cause supply and demand factors to become entangled, just as people like Tyler Cowen, Scott Sumner, and I have intuitively suspected in the case of Japan. The paper also shows, yet again, how many things we are still learning about the general behavior of the models, and their sensitivity to different assumptions and situations.

Update: Steve Williamson and Matthew Martin both chime in with good posts that play around with the implications of liquidity-trap New Keynesian models. Both posts show how little of the standard New Keynesian intuition applies with liquidity traps, and how little we understand about the true general behavior of these models.

Update 2: Someone also reminded me of this paper by Mertens & Ravn, who find that liquidity trap models can sometimes cause supply and demand factors to become entangled, just as people like Tyler Cowen, Scott Sumner, and I have intuitively suspected in the case of Japan. The paper also shows, yet again, how many things we are still learning about the general behavior of the models, and their sensitivity to different assumptions and situations.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar