|

| Survey Research at Work |

What should be kept in mind is that, like engineering, economics is a broad discipline that covers many different fields. Just as some engineers study computers and others study nuclear reactors, some economists study taxes, other study financial markets, and still others study how psychological biases should change the design of policy. So to use the chaos in financial markets as a reason to discredit all of economics is analogous to discrediting all of engineering on the count of a Fukushima disaster. While portions of macroeconomics may be made up of smoke, mirrors, and misleading standard errors, even a brief introspection can reveal why that is not representative of economics as a whole.

In economic models, people do whatever maximizes their self interest. However, this leaves no room for intellectual growth -- any new insight or strategy would have already been discovered by the omniscient agents! But people are of finite intelligence. As a result, their self-interest can be up for reinterpretation.

In this area, economists play the important role of introducing new *ideas* about policy. Precisely because people are not as omniscient as the agents in economic models, it's important that governments have a solid foundation on ideas to conceptualize and defend policies from critics. By introducing a new framework or a new empirical fact, economists can cast policy into a different light and redirect the conversation and agenda.

Let us first consider the canonical example of auction theory. Game theorists have been remarkably effective at designing auction mechanisms. The late Ronald Coase famously argued that the U.S. should auction off spectrum rights. Yet in his Congressional testimony, he was met with disbelief, with a congressman asking "is this a joke"? Later on, when the FCC changed its mind, it fell to economists (game theorists, no less!) to design the details of the auction. Designing such an auction is not a trivial task. Since it's advantageous to have radio frequencies in geographically contiguous areas, what a company is willing to bid on one spectrum in an area is dependent on whether it can win in other areas. Moreover, there are a host of protections you need to design. How do you stop firms from colluding? How do you make sure firms can't manipulate the bids to pay extremely low prices? When these issues were ignored in the Australian and New Zealand auctions, many hundreds of millions of dollars were lost.

Economists have also managed to change the way we talk about poverty policies in the United States. A common misconception is that impoverished people are just lazy, and that nothing can be done for them. And as a result, welfare just represents an unproductive transfer from the makers to the takers. However, survey data from the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan has shown that poverty is most often a transitory phenomenon, and that no, welfare is not about Cadillac queens or subsidizing sloth, but rather about providing insurance for a wide range of people who live on the threshold of poverty. The fact that the national conversation sometimes forgets this point is a reminder that economists do have an important role to play in shaping the welfare policy debate, and that neglecting this can have serious human impact.

And when we take a look at the the role of economists in analyzing aid and development, the impact is even larger. The foundations of international finance and the study of capital flows explains what kinds of aid are better than others, and why it's important not only to provide money but also personnel and expertise. On a micro level, pioneering experimental work, as popularized by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banjeree in their book titled "Poor Economics", has added an additional subtlety to the design of development policy. By integrating insights from psychology and political science, development economists like them have gone on to revise how to better provide fertilizers to farmers or how to limit the extent of patronage politics. These are all critical issues in the task of economic development, and it has fallen to economists to address them.

So far, I have focused on micro topics. But there are actually a surprisingly robust set of results about how emerging markets should handle capital flows. Stephen Salant (who is teaching me applied micro modeling this fall!) laid the foundation for speculative attacks on stockpiles of resources, such as oil or food. His model later led to Krugman's pioneering work on how currency crises happen, and the lessons from the literature on currency crises showed why external debt could be so harmful for developing economies. Anton Korinek has also made great contributions outlining the welfare arguments for avoiding external debt and currency crises. Indeed, those economies who had large stocks of external debt relative to foreign reserves were precisely the ones who suffered the most during the financial crisis. While it may not be a direct result, it is now clear to all emerging markets that a combination of external debt and exchange rate pegs can be extremely dangerous. And the absence of those two fault lines has put the emerging markets on much more stable footing during the current sell-off.

Even in the controversial field of monetary policy we're doing better. Back in the 1920's, it was thought that monetary policy should ease during the boom and tighten during the bust. This was called the Real Bills Doctrine, and ended up amplifying the business cycle. Doubt about the effect of Quantitative Easing is not equivalent to ignorance about money's effect on the macroeconomy. We might not be clear on magnitudes, but we at least know which way goes up and which goes down.

From a methodological standpoint, economists are valuable because we are trained to think about social issues through a quantitative and empirical framework. While other social sciences such as sociology and psychology are also known for their increasingly quantitative measures, economists are special because the variables we are interested in -- income, prices, population -- are easily measured and interpreted quantitative measures.

(As a digression, I was surprised that this notion of economics as socially applied statistics was completely missing from the conversation about economath. Without the work in mathematical statistics, economists would have been unable to do the measurements that we do, and the empirical studies that I describe above would not have been possible. I remember Miles Kimball joking with me that empirical macro is all about interpreting measurement error, yet without the work of generations of econometricians, we would not know of how to do that kind of analysis.)

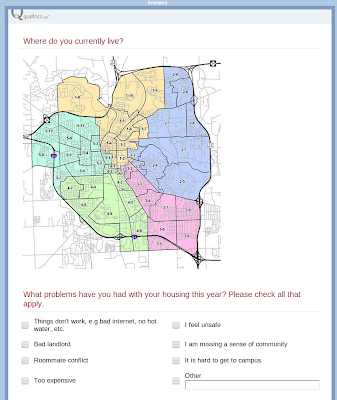

From a personal standpoint, I will also be contributing towards this kind of research this year. Since University of Michigan is a state school, we are of course very concerned about how all of our students -- across socioeconomic classes -- are doing. And therefore I will be heading a project to design a survey instrument and analysis methodology to measure how students are doing in the off campus housing markets and to identify the potential severity of this kind of socioeconomic segmentation. (See picture). While it may be true that my project will have various flaws, I still think of it as representative of the power of empirical economics. Identify problems. Collect data. Make lives better. Wash, rinse, repeat. And at least from personal experience, this mode of analysis -- of looking at bivariate relationships, of thinking about longitudinal effects -- is not as common among my fellow social scientists from psychology or political science.

This explicitly empirical tack built into modern economics is important because the alternative to a world with economists is not some non-partisan paradise. Rather, it will be filled by the Keith Olbermanns and Sean Hannities of the world, who rely instead on cheap rhetorical tricks instead of well grounded theory and empirics.

Yet in spite of my strong conviction that economists do create value for society, I do recognize that economics, on the most part, is not an experimental science. But that should not necessarily be seen as a flaw. Economists are tasked with evaluating policies that can play such a large role in the welfare of the masses. And once you know that a certain policy is harmful, it would be a profound breach of ethics to repeatedly apply such failed policy so that you could "replicate" and make the results "scientific".

I want to wrap up this post with a joke.

A physicist, a chemist and an economist are stranded on an island, with nothing to eat. A can of soup washes ashore. The physicist says, "Lets smash the can open with a rock." The chemist says, "Let’s build a fire and heat the can first." The economist says, "Lets assume that we have a can-opener..."The punchline suggests that instead of solving problems, economists just assume them away. But the real work of economics actually comes after the initial assumption. A real economist goes "..then if we had a can opener, we would be set. So let's go make a can opener." The joke misrepresents the work of economists by focusing on "opening a can" -- a task that has neither ambiguity nor great subtlety. On these issues, of course the hard sciences will be superior. But what if we asked a different question such as "how should we reduce carbon dioxide emissions"? In this case, there is no clear answer. But the economist would go "let's assume there were a price to carbon. Then the first welfare theorem means there's no inefficiency. So let's go price carbon!"

The big social problems of our day -- long term poverty, global warming, the middle income trap -- have few direct solutions, and any solution will affect portions of society in largely differing ways. And without economists to help work out the theory and empirics, how do you plan on tackling such dilemmas?

---

Update: Indeed, long term unemployment is a more severe problem than just an intellectual scruffle. But it really does seem that after the Great Recessions, economists are (perhaps rightly) viewed with more skepticism.