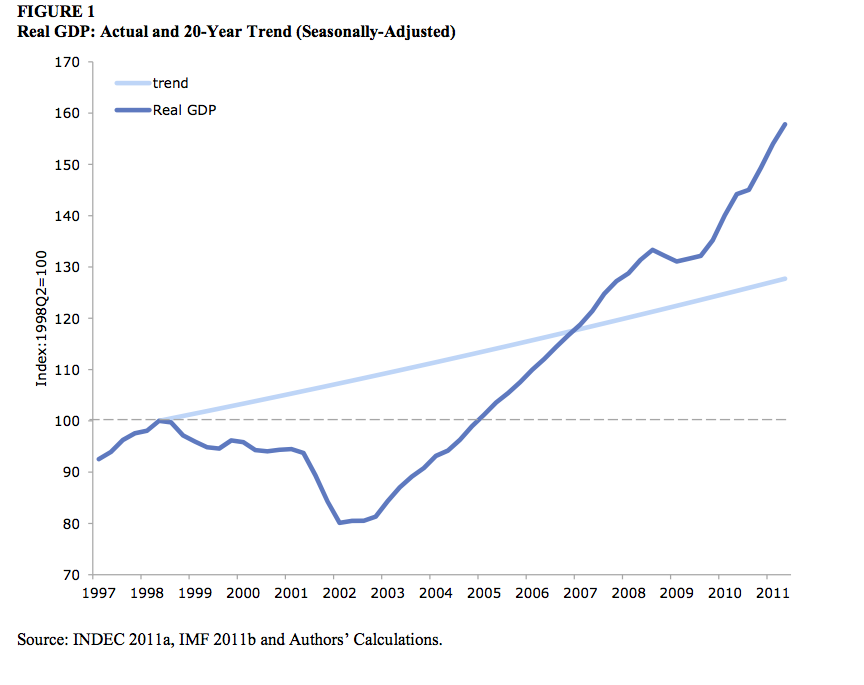

There are two reasons to think about what happens in the eventuality of a Japanese sovereign default. The first is that Japan's debt might be big enough, and its bond market reluctant enough, that it is forced to either default, hyperinflate, or go into severe austerity mode. In that situation, a default might be the best option. After all, after Argentina defaulted on its debt in 2001, its economy suffered for three years but then did quite well, substantially outperforming its pre-default trend:

That looks like a decently good macroeconomic scenario. And far from being an exception, this story is the norm:

So the precedent for a default is not apocalyptic. Whether this is better than hyperinflation I will leave unanswered, but it seems likely to be better than a long grinding period of austerity-induced stagnation. Also, note that austerity would redistribute wealth from Japan's young to Japan's already-comfortable older generations; a default, in contrast, represents a big transfer of wealth from the pampered old to the struggling young.

The second reason to contemplate a default is microeconomic. Observers of Japan's economy are nearly unanimous on the need for "structural reform". But Shinzo Abe's offerings on that front were extremely anemic. And given the huge edifice of special interests in Japan, and the weak political system there, we can probably expect little progress on that front.

Structural reform is needed because Japanese productivity is stagnant. Here's a graph, from Takeo Hoshi's much-cited paper:

Hoshi attributes the stagnant TFP to "zombie" companies - companies that continue to live only through repeated infusions of below-market-rate loans. These zombies, he claims, crowd healthy, productivity-growing firms out of the market. His research with Ricardo Caballero and Anil Kashyap supports this story.

My own suspicion is that low TFP growth is also partly due to poor corporate governance in Japan. Here is a blog post I wrote about that.

A third, and related reason for low productivity growth may be the high prevalence of family businesses in Japan. There is evidence that family businesses experience slower productivity growth than non-family businesses. In this way, Japan may be similar to Portugal; I encourage everyone to read this Matt O'Brien post on family businesses and stagnation in that country.

For structural reform, Japan would need a huge blast of "creative destruction". Zombies and family businesses would need to die en masse, and healthy, independently run companies would need to emerge. The U.S. got that kind of blast in the 1980s, but Japan is unlikely to slash regulation, open up trade, and let the corporate raiders into the henhouse. The equilibrium of entrenched political interests is too strong.

Only a big external shock is likely to be able to cause the kind of destruction needed to clear away Japan's economic ancien regime. A default would do the trick. Banks would go bamkrupt and be nationalized, and they would be forced to cut off zombies, which would then die en masse. If Japan's history is any guide, a huge burst of entrepreneurship would probably follow this die-off; witness the emergence of Sony and Honda after the shock of WW2.

So there might be some very good reasons for Japan to choose a sovereign default. But of course there would also be large costs. What would those costs be? I see three big ones: Human cost, inequality, and political risk.

The human cost could be a jump in the already sky-high suicide rate. A large number of Japanese suicides are men who lose their jobs. The close family structure of companies means that these men essentially lose access to their entire social support network. Combine this with a culture that is not very forgiving of failure, and you begin to see why a spike in unemployment might cause a large number of self-inflicted deaths.

Then again, this cost is not certain. A recovery of dynamism in Japan's economy might ultimately save more lives than it took. And human psychology is a fickle thing; it might be that in the wake of a default, unemployment might be seen as a natural disaster rather than an individual failure, and the suicide rate might even fall.

A more definite cost would be a rise in inequality. Once famed for being a middle-class society, Japan has experienced a rise in inequality over the past two decades; it is now less equal than Europe, though still more equal than the U.S. A default might change that. Family businesses might hold back productivity, but they also anchor the Japanese middle class; if large numbers of them went under, that middle class would be set adrift.

Finally, the biggest cost of a Japanese default would be political risk. As can be seen from Argentina's example, defaults are often followed by steep drops in GDP (and rises in unemployment) that last for two or three years. That might be bad enough to destabilize Japan's already weak political institutions, and prompt the fall of the post-WW2 regime. That in turn would likely involve violence, social disruption, and increased social repression. If the winners of the coup were the "authoritarian nationalists" - basically, Shinzo Abe and his crowd - then things might not be so bad, since those guys are generally responsible and committed to a strong, stable nation.

But if the victors were the "fanatic nationalists" - think of Toru Hashimoto and the guys in black vans - then Japan would be in for a very bad time indeed, and would quite probably revert to an unstable, violent, socially divided, repressive middle-income country like Thailand. That would be the worst possible outcome of a default.

So basically, a default would constitute a roll of the dice - a dramatic gamble that a collapse in the old order would be followed by a repeat of the kind of explosion of positive dynamism seen in the post-WW2 economic miracle or the Meiji Restoration. If the gamble failed, however, the consequence could be the end of the beautiful, peaceful, relatively free Japan that many of us have come to know and love.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar